To paraphrase Charles Dickens:

“It is the best of times, it is the worst of times, it is the season of Light, it is the season of Darkness, it is the spring of hope, it is the winter of despair, we have everything before us, we have nothing before us. . . . “

When genealogical research meets the patchwork quilt of state adoptions laws, the path to discovering our ancestors can be facilitated by enlightened politicians or stymied by draconian legislation. Isn’t it our birthright to know who we are and where we came from? In brief, Montana says yes, Texas says no.

Two years ago, I was contacted by a man wanting to identify his biological parents. He was not looking to meet them: if they were still living, they would be in their 80s or older. He simply wanted to know his family history. At first, I was dubious, never having researched Montana’s adoption laws, but ironically being involved with those from Texas at the time. My father-in-law (Robert) had passed away just two months earlier, and when my husband returned from clearing out his dad’s papers, he brought home a folder of correspondence that broke my heart.

The fact that Robert had been adopted from the Texas Children’s Aid Society in 1922 was the not-so-secret family secret. We all knew; however, everyone pretended that they didn’t, because he was not willing to discuss it. But with his death, the file of letters to the adoption agency, state legislators, lawyers, and judges was left to my husband. The folder contained a single sheet of paper labeled: “What We Know.” Precious little information followed: his birthday, location, a single sheet (heavily redacted) comprising his “case history,” and a copy of his adoption papers, held by the county Registrar of Deeds. The only birth information in the “deed” was a birth name — Joe Wilson — nothing of his biological parents.

Robert had spent the last 20 years of his life trying to find out if he had living biological relatives. He wanted to know who and where he came from. It is a universal desire. But Texas laws seal adoption records “forever;” it didn’t matter that well into his eighties, Robert certainly did not have living parents. And my husband, an avid genealogical researcher himself, had been able to pursue only his mother’s side. Letters to the Edna Gladney Home (the former Texas Children’s Aid Society) were met with stony refusals. Even though Robert was now dead, at age 88, they would not release an unredacted copy of his adoption so that his children could know their genealogical history.

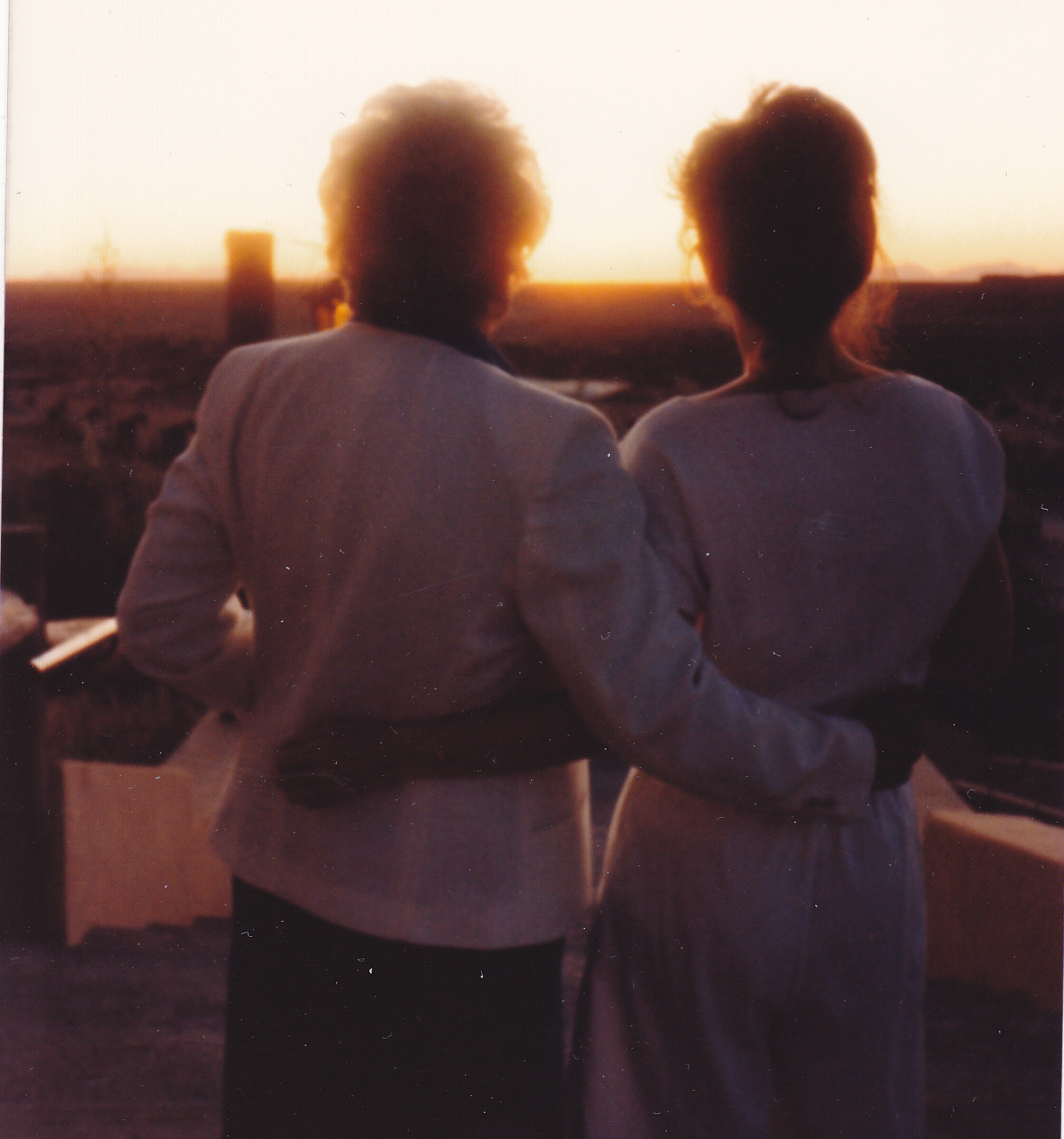

After reading hundreds of online postings from others desperately seeking their family stories but being completely rebuffed by the Texas laws, I noted there was only one exception to the ironclad rule: the presence of a genetic disorder. Hemochromatosis! This is a potentially deadly illness in which the body accumulates iron in vital organs. But if caught early enough, a few yearly phlebotomies keep it in check. Both my husband and his older brother have this disease. A doctor’s letter led to a court order, and within a month, we received an unredacted copy of the adoption records. Our resulting genealogical research led to a living aunt, dozens of cousins, and ultimately a family tree documented back to Colonial America. It also led to an emotional family reunion, forging strong new bonds.

Meanwhile, in Montana, I found not roadblocks to finding biological parents, but rather an enlightened law. For adoptions before 1967, such as the one I was researching, the adopted person is entitled to receive an original birth certificate at age 18. There are few changes covering the next 30 years, which entail a court order, but that is not difficult to obtain. The legal system recognizes the importance of medical history, whether or not a genetic disease is involved. And since 1997, barring a request from a birth parent requesting records not be automatically released to the adoptee at age 18, those records are indeed seen as a birthright and are provided upon request. If biological parents filed an objection upon the adoption, then the court order has to be issued, but again, the presumption is with the adoptee. Montana adoption records are not held by the registrar of deeds: children are not property whose lives are to be forever controlled by the wishes of their parents who have, for whatever reason, given them up for adoption.

If you are trying to find biological parents or seeking other biological family and would like some professional assistance in researching the various state laws, you are wise to contact a genealogy ancestry service. RecordClick’s professional genealogists can assist you in your search to find biological parents and family. Genealogical research can take us down a wide variety of paths, some more difficult to navigate than others. But finding birth parents and family, living and deceased, can be facilitated by knowledgeable genealogical researchers. May your search result in “the best of times . . . and the season of light.”

A professional genealogist and expert genealogy writer, Patricia (“Tricia”) Dingwall Thompson’s articles can be found in the New England Historic Genealogical Society magazine “American Ancestors” (Spring 2012), on Everton’s Genealogical Helper website, and serialized in the “New Hampshire Genealogical Record.” A number of her researched genealogies are housed in the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. Having taught high school Advanced Placement English for 38 years, Tricia now teaches genealogy classes through the Bozeman School District’s Adult Education program, and serves as Registrar for the Mount Hyalite Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution.

(photo credit Nancy Siddons-Daniels)